Dear Everybody,

I hope you’re physically well, feeling inspired, doing good for yourself and others. Me? I finally back in Ess Eff and I’m egging myself on, trying to get up early and write before the day gets too complicated. I know I haven’t posted anything in eight weeks. It’s August and I noticed my front steps were all wet this morning. My newspaper, which comes in a clear plastic bag, had big droplets on it and when I picked it up water fell on my socks. I can’t remember what the headline was but I’m feeling a damp sort of deja vu.

Now that I think of it, I doubt you even knew that I was gone. I never told you I was going anywhere, not that it mattered that you knew, but it’s just that I barely told anybody. I told my aged mother. I told my next door neighbor. I built a sprinkler system in the backyard with a timer so the plants would get watered. I sequestered my cars. It wasn’t a vacation except in the sense that I vacated my house. I left quietly, and you probably didn’t realize that my last three pieces were posted from Tokyo. That’s where I’ve been for the last two months.

"How odd," my old friend Boccaccio would say, “None of that stuff you wrote about had anything to do with Tokyo.”

"I know."

And then he'd say: "If you really were in Japan, why didn’t you write about Japan? How come you didn’t do any pictures like you did the year before? I thought the one you did about “hutsu” was interesting. I think you missed an opportunity."

I agree completely. I should have written about Japan and made artwork and done stories and essays about Japan while I was in Japan. The fact is, the last two stories I posted on my site were written years ago and lately I haven’t written much of anything about anything really, unless I count the stuff in my pocket notebook.

It’s become a habit with me, to write things down in little notebooks I carry in my shirt pocket. For over ten years I’ve been doing this, and I counted the notebooks the other day. I've got twenty-eight of them all filled up with my walking-around thoughts.

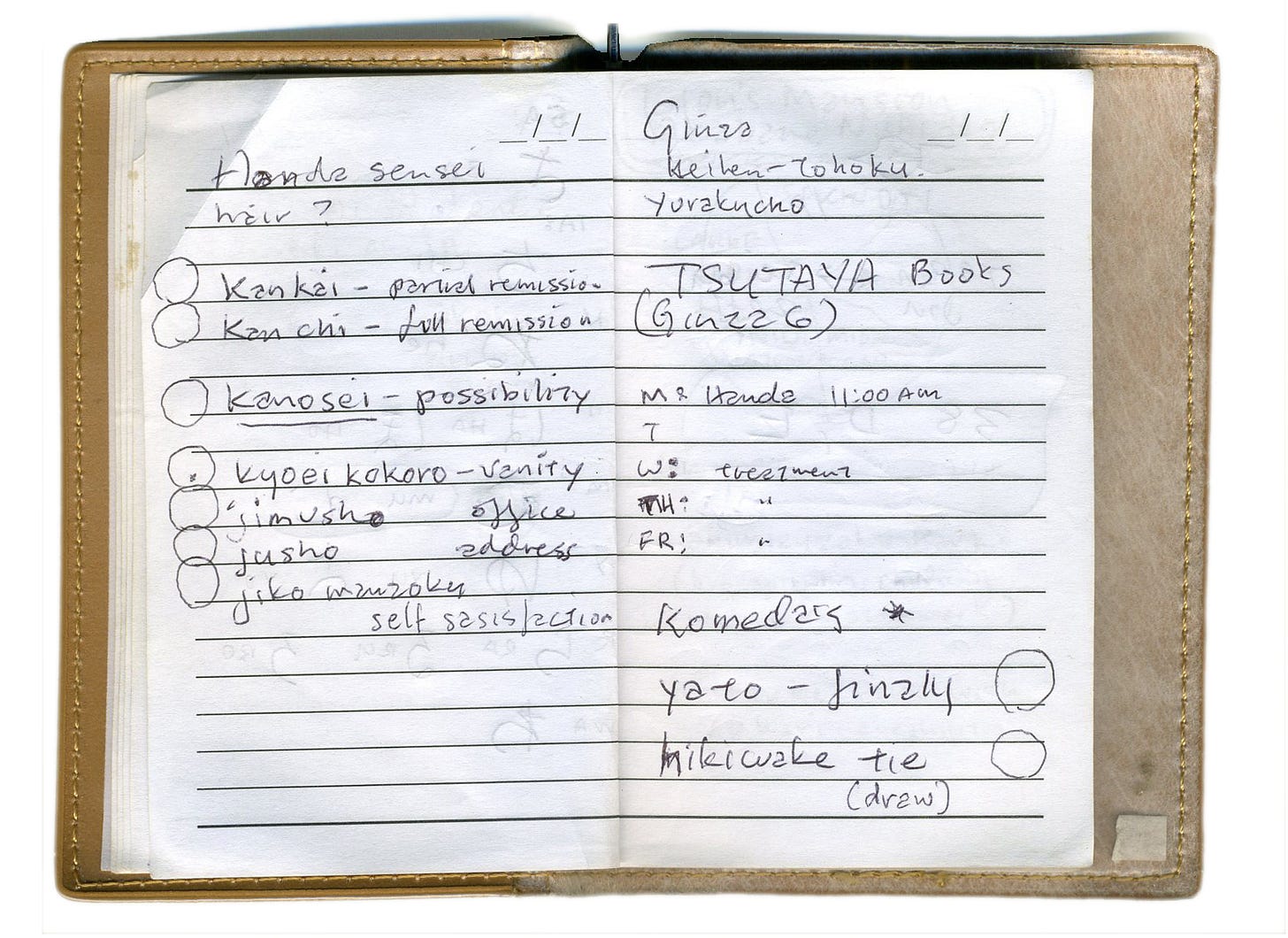

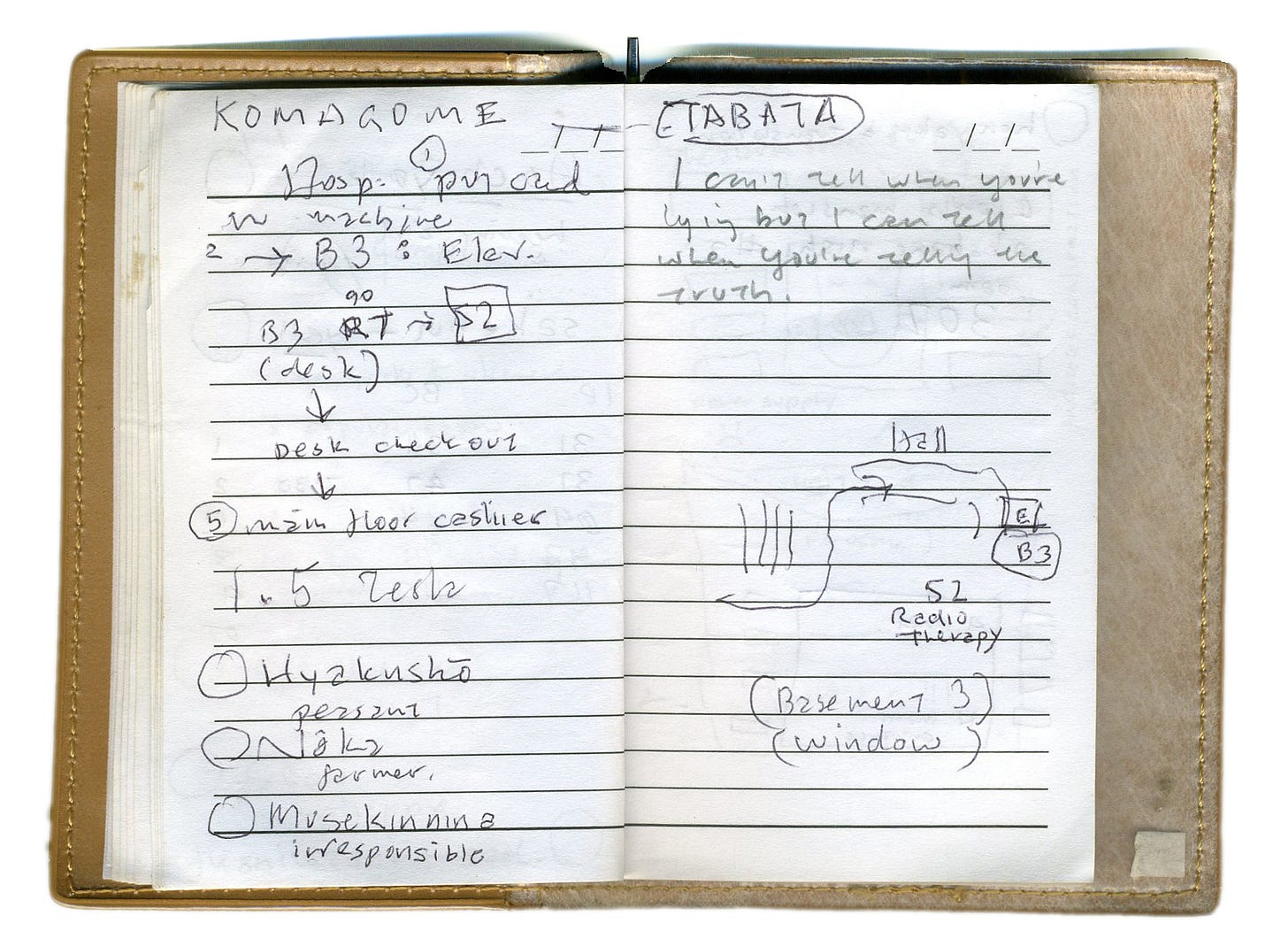

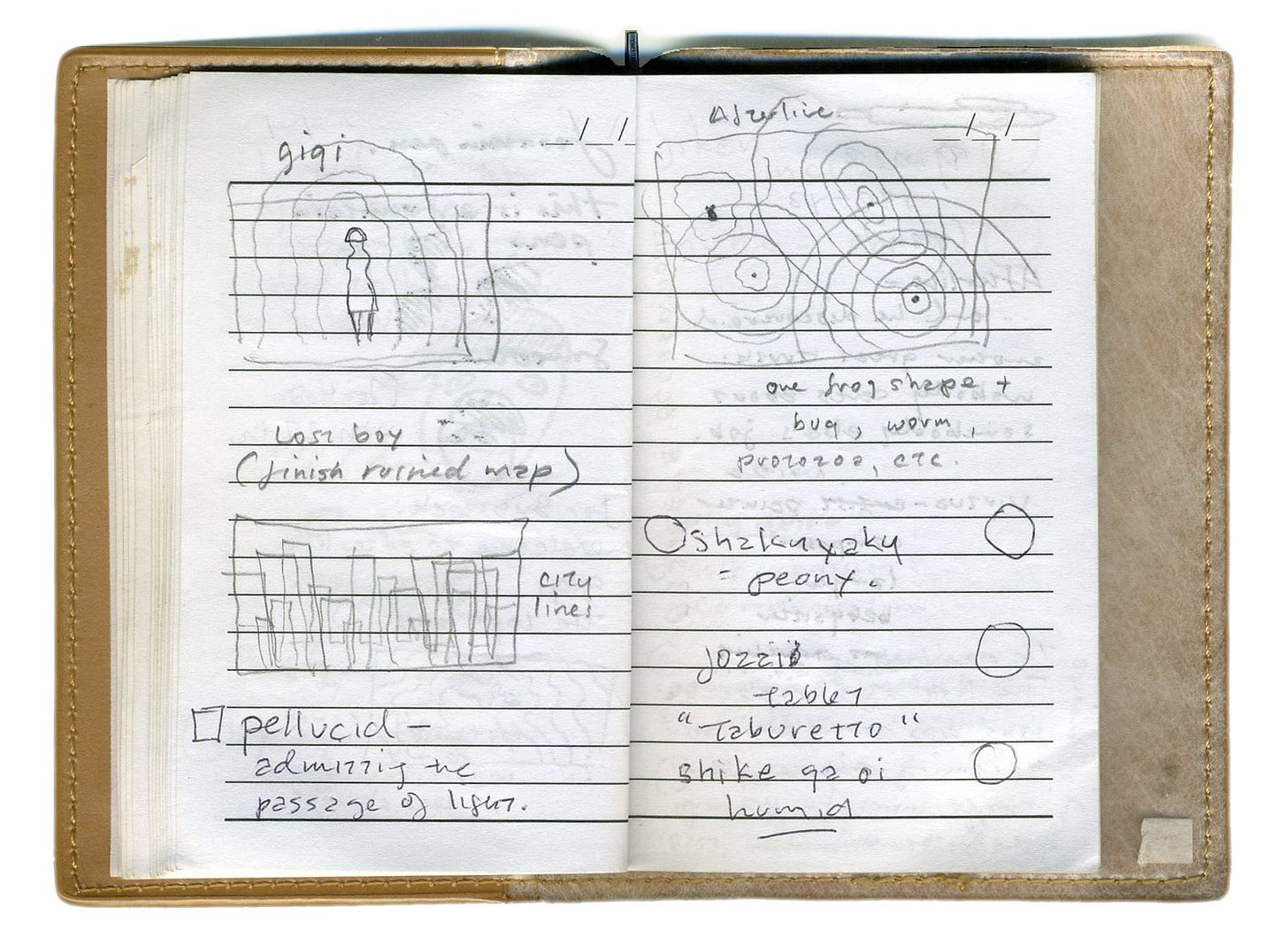

“My thoughts?” That’s a bit of a stretch. They’re more like scribbles, gripes, snatches of dialog, doodles, story ideas, shopping lists; jalapenos and fukujinzuke. You probably do it too if you’re a writer—write things down even before you know the point of it—marginalia, flotsam that has a way of drifting into the brain. This latest one, number 29, which I began in May and nearly filled up in Tokyo, is interspersed with doctor’s appointments, medical terms, train stations, Japanese words for misfortunes, obstructions, plights, expressions of gratitude, things I imagined I’d say but didn’t always get around to, things I’d jot down when I wasn’t smushed among the multitudes on a train, squeezed onto the Keihin Tohoku holding onto the ceiling strap, clutching my bag of bentos.

The reason for my trip to Japan was slipshod, unanticipated, ad hoc, complicated. It had to do with my Japanese wife who’d been there for several months, ever since she’d left to care for her aged mother.

My wife says her mother has “Alzheimer’s,” but I’m not sure that’s right. Alzheimer’s, regardless of whatever the medical definition is, suggests tragedy. I’m thinking of a movie about Iris Murdoch from several years ago called Iris. I don’t know if you’ve seen it, but at one point the actress who plays Iris says, “I’m sailing into darkness,” and that’s the image of Alzheimer’s I’ve had ever since; the idea that someone’s mind, my mind, my essential self, could float away in a boat while my still functioning body stays behind on the shore shitting into a wastepaper basket.

But my mother-in-law is not like that. She’s not tragic. She’s as cheerful as she's ever been. She’s convivial and talkative, and most of what she says makes perfect sense—at least to me(!) It’s just that her short term memory has shrunk to almost nothing. If you’re sitting with her and then you go to the bathroom, she’ll be strangely excited when you get back. “Hisashiburi desu ne!” she’ll cry. “It's been so long! Sit down, sit down!”

Within our little family circle we report to each other about Bachan’s (Granny’s) funny misunderstandings, or the way she’ll suddenly, extemporaneously, sing a song that nobody has ever heard before, or launch into a discussion with somebody who’s not present—or at least not visibly so—and when my sister-in-law asks who she was speaking to, the answer is always evasive: “Somebody you don’t know,” she’ll say. “An esteemed person (erai hito).” For Bachan, every moment is new you see, and I don’t mean to make light of her condition, but it always strikes me as a little bit beautiful, even desirable, to be continually surprised and delighted about everything, to have a mind that’s always floating back to the shore.

So, Bachan is bright and charming, but she also requires a lot of supervision and support. Most of this burden falls on my sister-in-law, and it’s only when my wife goes to Tokyo that Sis-in-law gets her well-deserved break.

That was the situation in February; my wife was there and I was here, marooned on the shore where I spent my time working on the house, paid the bills, took day trips to care for my own aged mother and, in the mornings, I tried to write. I was in the middle of making another pot of spaghetti to last another couple of weeks, when the text from my wife came in:

“Bachan is fine, I just got home from the hospital where I had a CT. The doctor thinks I have lung cancer.”

We talked on the phone for a few minutes after that. I told her to try not to worry until she got the real diagnosis. But a few days later the biopsy results came in and we learned it was small-cell carcinoma which, among the range of cancerous possibilities, is hardly a happy one. But it hadn’t spread very far, they said. It was what they term, “limited disease.” Her doctors seemed confident that chemo and radiation could kill it.

“I’ll buy a ticket right away,” I said.

“No. Please don’t come until I’m out of the hospital. I just want to be by myself. I just want to sleep.”

Later, my brother told me it was normal to feel that way. He said that when he had cancer all he wanted to do was hunker down and roll into a ball.

My wife said, “Don’t be insulted. I think it’s the best way right now.”

Three months went by before I landed in Tokyo with very few plans or preconceptions. She’d finally been released from the hospital and I figured my primary purpose was to lend my support to the family and try to be useful, and for a couple of weeks I was useful to the extent that I escorted her to and from her radiation treatments which were four train stops and a bus ride away from the house. And I helped, when they let me, with such manly tasks as fixing a dilapidated shed in the garden and repairing the front steps, but as the days wore on, I realized there weren’t very many useful things for me to do. Our son arrived soon after.

Bachan’s house, the family home, is in a place called Akabane (Red Feather) in north-central Tokyo. These days Akabane is most famous for its many izakaya. There must be thirty of them all clustered together in a ramshackle hive of late night revelry. Also, within a five-minute walk, you’ll find three department stores, numerous cafes, bakeries, a major train station with dozens of shops and newsstands, small hotels, a home improvement center, a covered shopping street called La La Land, a bus terminal, a major taxi stand where Tokyo’s glittering taxis cycle in and out. In fifteen minutes you can walk to the Arakawa, a river hemmed in by levees and green fields. Trails and bike paths surround the river’s edge.

After I accompanied my wife to the hospital, we’d eat at a local restaurant if she was up to it and I’d take her back home so she could rest. I had most of the day to myself after that and I’d wander the city, sometimes with my son and sometimes solo, going here and there, getting a drink or maybe two, browsing, jotting things down in my notebook.

“It’s a great chance to write about your thoughts and feelings,” Boccaccio would say.

“I know. But I don’t feel like it.”

The advice that writers hear over and over is true: "Write a little everyday." It’s like anything else really. The more habitual something is, the easier it becomes. I’ve skipped a couple months of writing now and it doesn’t feel habitual anymore. It feels strenuous, but the consolation is that I'm catching up on my reading. I can’t bear to watch TV, and I’d rather read than write. Writing involves thinking, while reading lets my mind sail into a different light. I started reading Japanese novels exclusively while I was in Tokyo, translations of course, and I’m still at it. It’s become a fairly serious study and I’m finding it quite interesting.

My wife’s condition is kind of okay, kind of not. She’s experiencing all sorts of delayed side effects from the onslaught of her treatments, and she nearly always feels tired and depleted. But there’s no sign of a recurrence which is the most important thing. Upon our return we got through the aggravating process of realigning with our local HMO and of meeting a new oncology doc. On the morning of her first appointment she showed me an article on her phone about a new sort of immunotherapy designed to keep her personal brand of cancer at bay. “Ask him about it,” I said, but even before she had a chance to, the doctor brought it up. Now we’ve embarked on an monoclonal antibody adventure that’s slated to last two years.

In case Boccaccio actually ever does read this, I want him to know I did manage to write one finished piece about Japan while I was in Japan, and it only happened because of a serendipitous meeting.

I’d walked to the Arakawa one morning and I was standing there looking out at the river, daydreaming, when someone spoke to me in English. A fellow about my age wearing a baseball cap and a striped shirt was very politely asking me to move so he could take a picture of a big stone monument that I happened to be standing in front of. I apologized in Japanese and, after he took his picture, I offered to take one of him and his wife in front of it. This led to a conversation, and he turned out to be a professor at a research institute. I said I was a writer from San Francisco, and one thing led to another and he suggested I write something for a magazine he’s connected with somehow. “I can’t write Japanese,” I said. “It doesn’t matter, you can do it in English.”

“But what subject should I write about?” I asked him. “How about doing something about your experience in Tokyo?”

I laughed, but Professor Sakagami gave me his business card, and I jotted down my email for him and figured that would be the end of it.

To my surprise, he sent me a note the next day repeating his wish that I’d write something for “New Food Industry Magazine,” and finally, just about four days before we were to depart I sat down and did it. My article was based, as you probably guessed, on jottings from my pocket notebook. “Ten Tokyo Impressions,” I called it.

On the evening of the day I sent my draft to the professor, I was taking the subway to visit an American friend who’s lived in Japan for nearly his entire life. I was standing, squidged in among a hundred people or so when I checked my messages. The email said:

Thank you for sending me a very nice essay of Ten Tokyo Impressions. An editor of New Food Industry has read your essay and told me that your article is very interesting, and should be published urgently.

“Urgently.” The other passengers in that crowded car must have wondered what made the foreigner burst out laughing.

So you see, in the same way you never know when disaster’s going to strike, you can never know when something nice is about to happen. The meaning of life is the unexpected. All you can do is the best you can. Getting up early will be the key for me. I have a few ideas, and I’m looking forward to writing some new stories soon.

Yours truly,

R.Bix

Really liked this. I am fond of memoir, “general musing”, essay. Look gorward to reading more of your words … and best wishes to your wife.

I have been receiving only a few of my substack emails these days, for unknown reasons, so I didn't see this until today when I visited the website. Oddly though, yesterday I was thinking that it had been a while since you posted anything. Also I thought about your wife though I know of her only from random references. I'm so sorry to hear about the cancer and I hope the therapy lives up to expectations. It's strange to read in the comments that this letter gave you trouble because it seems to flow so naturally. I enjoyed reading about your travels and everyday experiences. Even when describing such things your writing is captivating and your unique voice comes though. I think it's normal that you don't feel like writing considering all that's been going on. I haven't posted in several weeks but I really have no excuse besides laziness and lack of inspiration. Looking forward to your next piece, whatever form it takes, and I hope getting up early does the trick.